Imagine you spent two years building an incredibly complex Lego city with your friends, only to have the team leader decide to smash it all and revert to the foundation you had two years ago because they didn’t like the opinions of a few builders. This is essentially what is happening in the world of open-source display servers right now. Let’s dive into the technical drama between Xorg and X Libre to understand why this matters for the future of Linux and BSD operating systems.

To understand the current situation, we first need to look at what Xorg (often referred to as the X server) actually does. It is the core software layer that allows graphical interfaces to appear on your screen. Without it, or its modern competitor Wayland, you would just be looking at a black screen with text commands. Recently, a significant controversy arose regarding the Xorg project. Reports indicate that the maintainers planned to wipe out approximately two years of code commits. This decision was not based on engineering faults or bugs, but rather appeared to be motivated by internal politics. The plan involved a “rebase” to a version of the code from two years ago, effectively erasing thousands of hours of progress, bug fixes, and security patches contributed by developers who had fallen out of favor with the project’s leadership.

For a software engineer, the idea of reverting a codebase by two years is terrifying. In the world of software development, two years is an eternity. During that time, new hardware is released, new security vulnerabilities are discovered and patched, and performance is optimized. By reverting to an old state, the Xorg project risks re-introducing old bugs and losing compatibility with modern graphics cards. This erratic behavior sends a signal of instability to everyone who relies on their software. This is where the concept of a “fork” comes into play. When a project takes a direction that the community or other developers disagree with, they can copy the source code and start a new, separate project. In this case, X Libre has emerged as the alternative fork, aiming to preserve the technical progress that Xorg is threatening to delete.

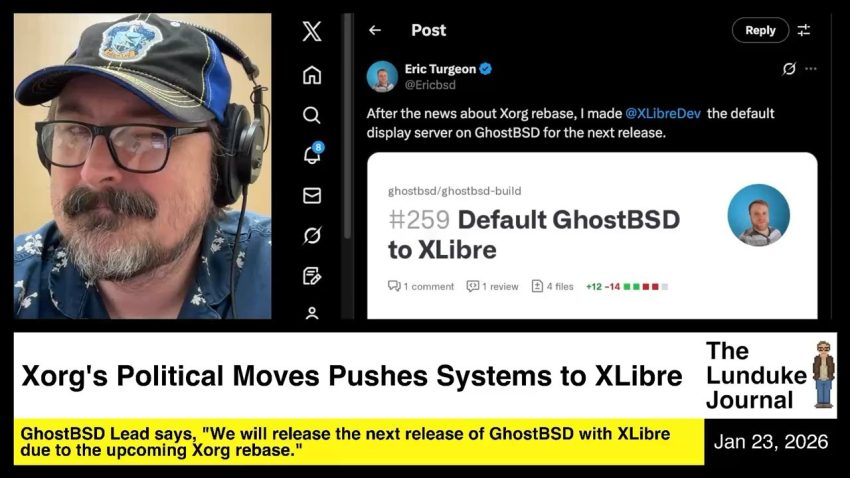

The consequences of this decision are already rippling through the ecosystem of operating systems. One of the first major projects to react was GhostBSD. GhostBSD is a user-friendly operating system based on FreeBSD, known for being stable and apolitical. The developers behind GhostBSD looked at the situation with Xorg and realized that building their operating system on top of such unstable software was a bad engineering decision. They announced that their future releases would switch to X Libre by default. This was not a political statement, but a technical necessity. They need a display server that retains modern features and bug fixes, and X Libre offers that stability. It highlights a crucial lesson in computer science: reliability is often the most valuable feature of any piece of software.

We are seeing a similar sentiment with Linux distributions like OpenMandriva. These projects generally try to stay out of social politics and focus purely on the technology. When a critical component like the display server becomes unreliable due to non-technical reasons, system integrators—the people who bundle all the software together to make an operating system—lose trust. The transcript suggests that this might be part of a broader trend where larger organizations, such as the X.Org Foundation and Red Hat, are actually okay with Xorg failing because they want to push users toward Wayland, a newer display protocol. However, the aggressive nature of these changes seems to be pushing users toward X Libre instead of Wayland, creating a fractured environment.

From a technical standpoint, X Libre is reportedly flourishing. Since the fork occurred, it has seen a high volume of commits, security improvements, and bug fixes—potentially more activity in a few months than Xorg saw in years. This is what happens when developers focus on code rather than ideology. For you as students, this serves as a case study in project management. When you prioritize external factors over the quality of your engineering, you risk alienating your user base. The migration of GhostBSD and potentially OpenMandriva to X Libre proves that in the end, technical merit and stability usually win. People just want their computers to work, and they will choose the software that guarantees the best performance and the least amount of drama.

As we look toward the future of open-source operating systems, specifically throughout 2025 and 2026, we should expect to see more distributions making the switch. The “slow roll” of release cycles means this won’t happen overnight, but the momentum is shifting. If Xorg continues to make rash decisions like wiping years of progress, it will become obsolete, not because the technology was bad, but because the governance failed. The rise of X Libre demonstrates the beauty of open source: if the main project fails you, you have the freedom to take the code, fix it, and build something better.

In the fast-paced world of technology, trust is a currency that is very hard to earn and very easy to lose. The situation with Xorg and GhostBSD teaches us that technical decisions should primarily be driven by engineering goals, not political motivations. As you continue to learn about coding and systems, remember that the stability of your project depends on the logical foundations you build. I recommend you try downloading a live image of GhostBSD or OpenMandriva to see these systems in action. It is a great way to understand how different components like the display server interact with the rest of the operating system.